Source of article The Jury Room - Keene Trial Consulting.

The U.S. Department of Justice defines hate crime as “the violence of intolerance and bigotry, intended to hurt and intimidate someone because of their race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, or disability.” While the documentation and awareness of hate crimes is essential, we also need to understand the differences in the numbers we see reported on hate crimes, increases and decreases for specific types of hate crimes, and what those shifts in numbers actually mean. We often see comments about one kind of hate crime being more “important” than another due to a spike in frequency. Today’s article points out that it is likely unwise to arrange the badness of hate crimes in any sort of hierarchy. To modify an existing meme just a bit, “hate is hate”.

This is a fairly dry article but it contains useful information on the documentation of hate crimes and the limitations of the reporting used to give us those numbers. The writer starts out by telling us there are 4 general sources of information documenting the prevalence of hate crimes.

- Victim reports to community anti-violence organizations.

- Community surveys conducted with oversampling of sexual and gender minority respondents.

- Data from local law enforcement agencies compiled annually by the FBI.

- And, surveys conducted with national probability samples.

The author believes it is important to understand that hate crimes are under-reported and different things will be reported to different documenters. Each of these information sources may well report their data accurately, but none of them is believed to be completely accurate. Here are some of his history of the data collection process and cautionary tales on how to evaluate hate crimes data by being aware of the source:

When data is reported by community organizations and anti-violence projects

Numbers gathered by these groups will likely be higher than those reported by law enforcement since victims may feel safer reporting crimes to these groups. Additionally, they are looking for evidence not just of a crime, but of the reasons for it—not something that law enforcement necessarily finds as central to their duties.

Prior to 1990, data was collected somewhat haphazardly and with little consistency between what information was collected from community to community. This changed in 1990 when data collection was standardized so it could be compared year to year.

Since 1995, data for crimes has been reported by gender identity as well as sexual orientation. For 2015, the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP) reported 1,253 incidents of hate crime against sexual and gender minorities as well as those with HIV (data was from 13 local member organizations in 12 states).

In short, this data provides valuable information about victims, perpetrators and crimes in specific cities. It is likely to include crimes unreported to criminal justice authorities and thus missing from FBI data. They do not include data from people who are in prison, those in rural areas, those who keep sexual orientation or gender identity secret, and those who simply feel uncomfortable reporting victimization to a community agency.

When data is reported from survey studies from academics and community-based advocates

Reports from these agencies are seen as an important estimate of the number of hate crimes that have occurred in a particular city in a specific year. However, the numbers are seen as low estimates since not all such crimes are reported to the agencies responsible for creating the reports. Earlier survey studies used non-random samples (that is, people volunteered or were surveyed in large groups like schools or churches) and their generalizability is limited. Early studies also did not identify data based on transgender versus cisgender status.

More recent surveys (again, these were not random samples) have shown that hate crimes occur in roughly one-fourth of transgender respondents up to about one-third of transgender respondents. In brief, this data documents the idea that hate crimes exist and allows examination of the demographic, social and psychological variables associated with victimization. Data quality varies widely and the prudent user needs to be aware of that reality.

When data is reported from FBI Hate Crimes Statistics

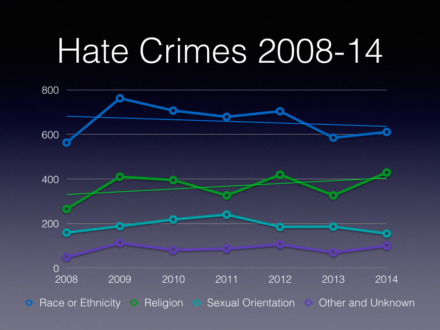

This data began to be collected in 1990 with 4,755 hate crimes reported for 1990. In 2013, the FBI began to also track hate crimes based on gender identity. They reported few of these sorts of crimes for a national database although the number is steadily raising. In 2013, 31 gender identity crimes were reported. [Gender identity refers to whether you see yourself as male or female and not whether you were born as male or female. Typically, the term “gender identity crimes” means crimes that were committed against someone because they were trying to ‘pass’ as a different gender or were thought to be trying to ‘pass’.]

In 2014, 98 gender identity crimes were reported and in 2015, 114 gender identity crimes were reported. The author says this data is likely under-reporting the actual incidence of hate crimes since participation of local law enforcement agencies is entirely voluntary; in order to report them, the local agency has to recognize they are seeing a hate crime; and many people never report their victimization to the police.

In short, the FBI data is valuable in that it contains only those incidents that have been identified by local law enforcement authorities as meeting criteria for a hate crime. As mentioned above, this data is plagued by under-reporting and is known to offer a lower estimate of hate crimes occurring in any given year.

Population-Based Surveys with National Probability Samples

The advantage of these surveys is that (since they are probability samples aka large and randomly selected participants) they are generalizable but collecting this data is expensive. Most researchers use government-sponsored surveys with large samples—like the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), to take advantage of the larger populations of sexual and gender minority hate crime survivors already in the sample. Differences in how the FBI categorizes hate crimes versus how the NCVS categorizes hate crimes result in widely differing numbers and reflect how many victims never report the hate crimes to law enforcement.

For 2012, the NCVS estimate of nonfatal hate crime victimization was 293,800 (about 13% of these were based on the victim’s sexual orientation). The author provides some other survey data that show anywhere from 12% to 32% of lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender adults have been abused due to their sexual orientation. Since these surveys did not measure exactly the same things, the ability to compare their findings is limited.

In short, this data avoids the underreporting of hate crimes issue in the other databases but you will have to ensure they are based on very large samples (and the NCVS data will be).

The author urges users of hate crime data to be aware of the nature of the data source on which they rely and its accompanying strengths and limitations. From a litigation advocacy perspective, it is important to know the strengths and limitations of the various databases so that you can educate jurors on which numbers are the best estimate of actual occurrence as they consider your case. Like understanding the problems for Black men encountering police and law enforcement—jurors who are not personally aware of the prevalence of hate crimes will need to be educated on that reality.

The implications for criminal cases involving allegations of hate crimes is pretty clear. While Defense attorneys may emphasize FBI numbers and say the conduct was not one of these rare hate crimes but rather one of the unfortunate confrontations that are seen every day.

Prosecutors will want to embrace the NCVS data and stress the reluctance to report hate crime victimization. We are reminded of the old saying that when you hear hoofbeats, you should expect to see a horse, not a zebra. The question is in part one of whether hate crimes are rare or not.

The public resistance to the idea that we live in a society with high levels of bias and unfairness is a significant barrier to accepting hate crimes. Prosecutors should consider avoiding indictment of society by talking about how common hate crimes are, and focusing on the elements of conduct that are in the hate crimes statute. Most people don’t want to believe that this is an epidemic, but they are more readily willing to see malevolent conduct, and struggle to find an explanation that makes sense to them.

This Defense approach would likely also offer the argument that the victim was in the wrong place at the wrong time. The Prosecutor can argue that this hate crimes are an epidemic and ask the jurors to send a message as to whether they want this criminal behavior condoned in their town. (Visit our Simple Jury Persuasion: Not in my town! post to see how this would work.)

Herek, GM 2017. Documenting hate crimes in the United States: Some considerations on data sources. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(2), 143-151.