Source of article The Jury Room - Keene Trial Consulting.

When litigation cases rely on science or highly technical information, it is critical to help jurors understand the information underlying the case at a level that makes sense to them. If they do not understand your “science”, they will simply guess which party to vote for or “follow the crowd”. Here’s an example of what happened when scientists “followed the crowd” to see what fields of science were seen as most precise (and therefore reliable).

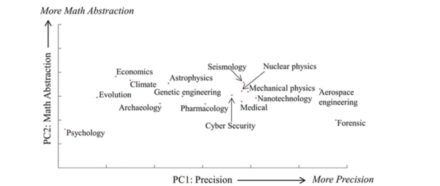

You can see from the graphic illustrating this post that too many people are watching CSI shows on TV. When forensic science is more “certain” than nanotechnology or aerospace engineering, and even mechanical physics—we have a problem! The authors actually agree with us in this press release:

“The map shows that perceptions held by the public may not reflect the reality of scientific study,” Broomell said. “For example, psychology is perceived as the least precise while forensics is perceived as the most precise. However, forensics is plagued by many of the same uncertainties as psychology that involve predicting human behavior with limited evidence.”

Be that as it may, when these researchers from Carnegie Mellon set out to see which branches of science the public feels most certain about—that is what they found. It is part and parcel of the frustration we often see from our attorney-clients when what they have presented is not what our mock jurors have retained.

We’ve also talked about the newer findings of political polarization coloring reactions to almost everything. The researchers also found political differences in the evaluation of whole fields of science here (again quoting the press release from Carnegie Mellon).

While political affiliations are not the only factor motivating how science is perceived, the researchers did find that sciences that potentially conflict with a person’s ideology are judged as being more uncertain. “Our political atmosphere is changing. Alternative facts and contradicting narratives affect and heighten uncertainty. Nevertheless, we must continue scientific research. This means we must find a way to engage uncertainty in a way that speaks to the public’s concerns,” Broomell said.

In other words, people believe what they choose to believe and you can’t predict how they will engage or not engage. And finally, they also make this comment which we are hearing more and more in the mass media—essentially, the responses these participants gave have no apparent relation to facts.

However, our results also suggest that evaluations of specific research results by the general public (such as those produced by climate change, or the link between autism and vaccination) may not be strongly influenced by accurate information about the scientific research field that produced the results.

This is an area of lament from many who deal in data and facts. We are living in a post-expert world (and some would say post-truth and post-facts). So what are you to do?

From a litigation advocacy perspective, this study tells us how important it is to make scientific research relevant and common-sense (or even counter-intuitive) to your jurors. They need to understand it and have it make sense to them or be allowed to revel in the counter-intuitive nature of the findings.

Feeling comfortable with the “science” (whatever it may be) is a much better way to ensure consistency from your jurors than relying on the chart illustrating this post to predict how listeners will react to the particular science upon which your case relies.

Broomell, S., & Kane, P. (2017). Public perception and communication of scientific uncertainty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146 (2), 286-304 DOI: 10.1037/xge0000260

Image taken from the article itself