Source of article Jury Insights.

Moral Conundrums and

Persuasion

Alan J. Cohen, PhD, Jury Insights

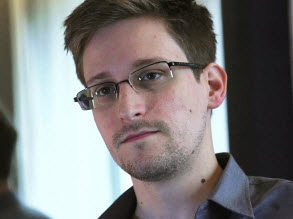

Edward Snowden

Edward Snowden – A Moral Conundrum

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor

Whistle Blower Hero, Terrorist, Traitor

Cowboy Hacker, Foreign Spy in Chief

Good Man, Bad Man, Robin Hood Thief

Morally speaking-who is your client, and what

is your case about?

Most people are a little perplexed when facing questions of

conflicting situational morality; that is, the very kind of moral questions

that reside in many cases making it past summary judgment motions.

Edward Snowden is a pretty good example of a person whose

actions present a situational moral conundrum. Imagine taking the position of

arguing Snowden is a textbook example of a whistle blower to an audience of

jurors with a point of view that Snowden is a traitor, and then imagine the

opposite.

Attorneys seek jurors who have favorable moral biases to his/her

side of the case, and who are resistant to changing their position. The

attorney seeks to remove jurors adverse to the case, and who are resistant to

changing position.

We know the mind resists changing a position already taken.

Check out these PsyBlog articles that discuss some common issues

in dealing with resistance to persuasion.

Nine ways the mind resists

persuasion.

Balanced arguments are more

persuasive.

http://www.spring.org.uk/2010/11/balanced-arguments-are-more-persuasive.php

One takeaway for the attorney is that it is a risky strategy to

attempt to scare, seduce or manipulate someone into changing a mindset.

When I started studying hypnosis as a practicing

psychotherapist, I thought I was going to learn about mind control. Paradoxically,

I learned that the basis for helping someone to “change” through

hypnosis was in helping the person become unchained from rigid attachments and

become receptive to seeing things from a different point of view. The

psychotherapist cannot just suggest/command someone to stop doing one thing and

start doing another. The therapist has to discover some motivational foothold

receptive to change already resident within the person.

Looking at it another way, it’s easier to scare a person into

not changing– becoming more rigid and resistant– than it is to get the person

to change. And, if you, as the persuader, come across as someone you

threatens the equilibrium for that person, you will encourage their

resistance.

If you, as the persuader, cannot deeply understand the

listener’s emotional and moral attachment to an adverse mindset, it’s going to

a rough road to making a convincing persuasive argument.

In old psychotherapy parlance, people resist change because they

are defended against the anxiety the change represents. Every position we take

serves as self-assertion and a protective measure.

We all develop life skills that help us navigate morally confusing

waters based on our biology, experiences and teachers.

When we seek to “change someone’s mind,” we are often

entering into territory that butts up against self-identified notions of what

it means to be a good or bad person–what’s right and wrong.

If the person doing the persuading cannot reach the listener’s

self-identification to remain a good person, it’s a lost cause.

Since most litigation presents two sides of a story, it is

important to embrace the “moral conversation” about the inherent

choice. The jurors are free to choose, and they need clarification of the moral

nature of the choice, and why they should morally identify with the choice for

your side of the argument.

Many cases in litigation have an Edward Snowden somewhere in them.

It’s a kind of “Where’s Waldo” game. You have to find the Waldo

of conflicting situational morality. You, as the attorney, at some point

in the “conversation” of voir dire and opening statement need to both

clarify and polarize the moral conundrum in your favor. But your

timing must acknowledge the listener’s capacity and readiness to integrate your

side’s moral premise. If you and the jurors do not harmonize, you’ll be

just as unsuccessful as a marital partner telling the other to stop smoking.