Source of article DOAR Litigation Consulting.

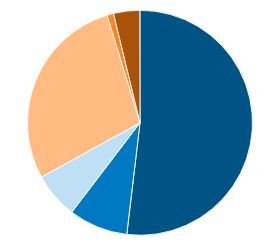

As internet use and social media become more and more prevalent, In a prior study,[2] jurors in 15 criminal and civil trials completed questionnaires distributed by the judge after the conclusion of the trial. These questionnaires assessed jurors’ use of new media during the trials, as well as the “old-fashioned forms of misconduct,” such as discussions about the case with family and friends and discussions with fellow jurors prior to deliberations. Results showed that only a very small number of jurors admitted to engaging in the old-fashioned forms of misconduct (6% discussed the case with family and friends; 10% discussed the case with fellow jurors prior to deliberations) and none reported using new media during the trial. One can imagine, however, that jurors were likely hesitant to admit in a courtroom that they had engaged in misconduct. So we wondered – how can we get to the bottom of this? Is it possible to get jurors to admit to something they know was wrong? We learned that it is indeed possible! Using an anonymous online survey, we investigated whether jurors had engaged in four types of misconduct: 1) online research about the case/parties involved; 2) posting about the case on social media; 3) discussing the case with family and friends while the trial was ongoing; and 4) discussing the case with other jurors before deliberations began. More than one half of the respondents said they had done online research about the case during the trial. Judicial instructions did not seem to prevent this behavior: 47% of those who reported having been instructed not to do online research[3] (143 of 305), still admitted to it. The most commonly searched topic was the law, followed by the judge and news articles about the case. Note: respondents were instructed to “check all that apply” Most respondents did research because they were curious and because they wanted to understand the law better and make an informed decision. Note: respondents were instructed to “check all that apply” We also wanted to know whether the jurors who engage in traditional misconduct are the same jurors who engage in online misconduct. As it turns out – they are. Nearly three-quarters (70%) of those who engaged in online misconduct also engaged in traditional misconduct. In comparison, only 30% of those who did not engage in online misconduct engaged in traditional misconduct (p < .001). This research is the first of its kind. By using an anonymous online survey, we were able to increase the likelihood that respondents would disclose misconduct. Results are consistent with what we hypothesized – even when they are instructed not to, jurors are still engaging in misconduct during trial. Attorneys: Consider how information that can be accessed online by jurors impacts your trial strategy even when it is not introduced during the trial itself and adjust your strategy accordingly. Assume that jurors are likely to access that information, share it with other jurors, and have it in some way impact their decision-making.According to this research, those who are most likely to engage in misconduct are younger non-Whites with College degrees. Also, males were more likely than females to do online research and discuss the case with family and friends. Why are they doing it? Because they are not understanding the law as it is explained to them in court! More than one half of those who did online research (56%) said that they were researching about the law. When asked why they did online research, curiosity (57%) and wanting to better understand the law (49%) were the most common reasons given. Has the advent of new media increased juror misconduct? Not necessarily. We expected that since so many people are addicted to their phones and computers, the likelihood that jurors would engage in misconduct may be higher than in the past. These results, however, suggest that may not be the case. Rule-breakers are rule-breakers – those who engage in misconduct are doing so by whatever means possible. It’s not the advent of the internet and new media that lead jurors to engage in misconduct – it’s their thirst for additional information. Back To Top Respondents represented jurors from 43 states: Respondents were asked to report their ethnicity, and were instructed to “check all that apply”: About one-fifth of respondents (19%) reported being of Hispanic/Latino background. Which form of social media do you currently use most often? Facebook was the most commonly used social media site.

[2] Hannaford-Agor, P., Rottman, D.B., & Waters, N. L. (2012). Juror and jury use of new media: A baseline exploration. Executive Session for State Court Leaders in the 21st Century, 1. Retrieved from http://www.ncsc.org/ [3] 54% of respondents remembered being instructed not to do online research, 33% did not remember being instructed, and 13% were not sure. [4] 62% of respondents remembered being instructed not to do online research, 27% did not remember being instructed, and 11% were not sure. [5] 56% of respondents remembered being instructed not to do online research, 28% did not remember being instructed, and 16% were not sure. [6] 56% of respondents remembered being instructed not to do online research, 30% did not remember being instructed, and 14% were not sure. [7] Since respondents were instructed to “check all that apply,” 16 of those in the White category also reported being at least one other ethnicity. [8] Because men outnumbered women by about 2:1 in our sample, we weighted gender for this analysis to reflect a more normal distribution of 1:1. The post Juror Misconduct: More Prevalent Than We Think? appeared first on DOAR.

How do we quench that thirst? Perhaps we should think about whether there are ways to give jurors more instruction on the law at an earlier stage in the trial. When jurors are not given instructions on the law or definitions of the elements of the alleged crimes until the very end of the trial, it is no wonder they feel as though they need to go elsewhere to investigate for themselves.

Using Amazon Mechanical Turk, DOAR conducted a survey of 562 people (68% male, 32% female) who reported that they had served as jurors in criminal and/or civil cases.