Source of article The Jury Room - Keene Trial Consulting.

We’ve written about CRISPR (aka human gene editing) before, and wanted to share this new survey with you. When last we blogged, it was to cover the Pew survey on fears about gene editing (and the potential for creation of a super-human). As you can imagine, there was some ambivalence over whether this was a good thing, as well as concerns about the creation of a society where genetically enhanced people ruled those who were not genetically enhanced. Here’s what we wrote a year ago: .

We’ve written about CRISPR (aka human gene editing) before, and wanted to share this new survey with you. When last we blogged, it was to cover the Pew survey on fears about gene editing (and the potential for creation of a super-human). As you can imagine, there was some ambivalence over whether this was a good thing, as well as concerns about the creation of a society where genetically enhanced people ruled those who were not genetically enhanced. Here’s what we wrote a year ago: .

You may be surprised at how ambivalent the public is about using these new tools. As Pew says, “Americans are more worried than enthusiastic” about how these tools will be used. And, as this technology veers more and more into public awareness, being aware of the ambivalence with which Americans view this ground-breaking technology is going to become increasingly important for trial lawyers.

So we were surprised to see a new headline in the online publication The Verge saying that ⅔ of Americans now approve of human gene editing to treat disease. It seemed odd since just last year, Pew’s survey told us this about sick little babies:

Even when it comes to gene editing with the promise of helping prevent diseases for their own babies

And now ⅔ of Americans support gene editing? It just seemed like too sudden a turn around. And—as it turns out, it was. You have probably figured out by now that this is just the latest in a string of directives from us to go to the original source to make sure things are interpreted correctly in secondary source materials.

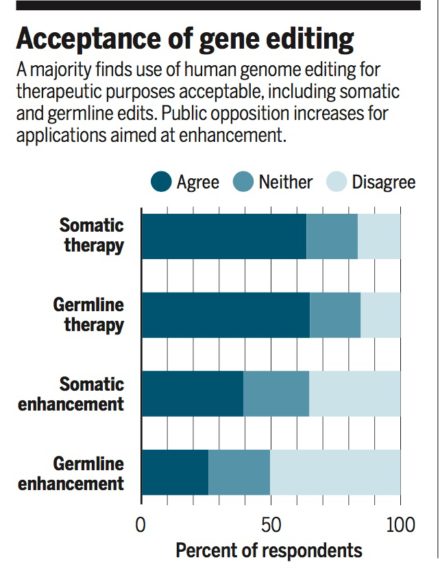

While the Verge article is based on the full survey results, it does not accurately reflect the ambivalence in the actual survey published by Science Magazine. The graphic illustrating this post shows you that what the headline writers over at The Verge did was to count those who supported human gene editing for specific use as a therapeutic tool to correct disease in human beings. But that leaves out a big part of the picture.

This headline does not include the concerns of those who don’t want the changes to be hereditary and thus change the human germline [aka, these changes would now be inheritable] down the road—which would ostensibly mean that if you are going to have gene editing done, you must either be a male or agree never to have children if you are female so that the germline remains unchanged by human intervention.

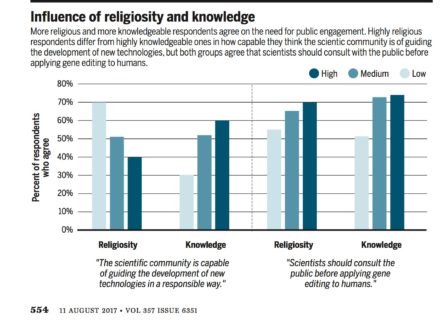

And, as you might intuitively predict, what the Science Magazine survey really showed us was that people who had high levels of knowledge on gene editing were more likely to support its use, while those who were religiously active were less likely to support the use of gene editing on humans due to ethical and moral concerns. What both groups agreed on, however, was that scientists should not make these choices alone. Both groups wanted scientists to somehow “engage the public” in a dialogue so that the eventual use of human gene editing would be one that reflected the concerns and wishes of all of American society. That’s a pretty tall bar.

We know that how you ask a question makes a huge difference. If someone is asked whether they think gene editing should be used to protect people from hereditary diseases, they may initially agree. However, when you then ask if they would agree to allow those changes to ‘permanently change the human germline’, you see more resistance to the entire process of human gene editing. As we said back when we blogged on the Pew survey of American attitudes toward gene editing,

From a litigation advocacy perspective, these responses are not necessarily intuitive. While we might intuit that allowing babies to be born without diseases would be a positive thing, respondents did not necessarily agree. They see it as being more complex. Although the parents of that baby struggling with a serious disease would likely strongly support the new technology for helping their child, others might well say “that sounds good, but this is a slippery slope and where will it lead?”.

As with all “hot button” issues, this is one that will require careful pretrial research to identify the most effective way to tell a story that will not set off knee-jerk morally based reactions to the use of new technologies. People want to feel safe from disease, but also from a world where science fiction movies come to life. Equally uncertain is how people see the role of government in nurturing innovation while protecting the public from science run amok.

We think those recommendations still make sense today. When you have an exciting whiz-bang technology like CRISPR, you may get so excited about it that you presume jurors will be excited (and support your case) too. But slow down—with any great advance in technology, there is also often great fear, so do some pretrial research to see how mock jurors respond to your presentation of the technology. It’s likely going to be a pretty complicated response that will require refining your presentation in ways you might not predict.

Dietram A. Scheufele, Michael A. Xenos, Emily L. Howell, Kathleen M. Rose, Dominique Brossard, Bruce W. Hardy. U.S. attitudes on human genome editing. Science Magazine, 11 AUGUST 2017 VOL 357 ISSUE 6351.

Images taken from Science Magazine article cited above